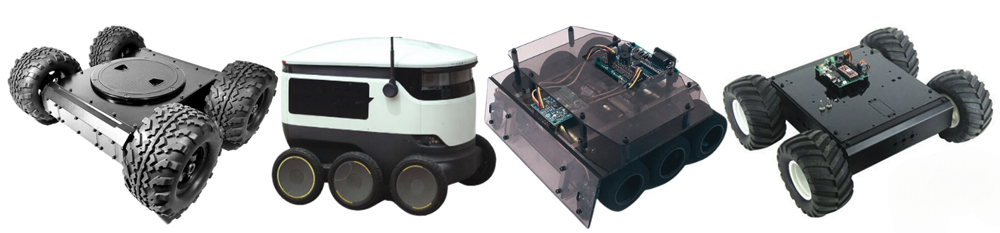

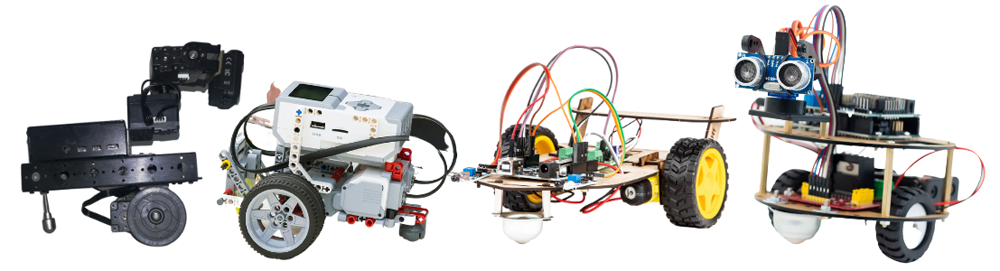

Designing a mobile robot and wondering what wheels (and how many) you should incorporate? You've come to the right place. Mobile wheeled or tracked robots have a minimum of two motors which are used to propel and steer the robot. Hobbyists tend to choose skid steering (like a tank) because of its simplicity of design, incorporation, and control. A three-wheeled robot’s third (rear) wheel usually prevents the robot from falling over. Four-wheeled robots have either two or four drive motors and use skid steering. Six-wheeled robots most commonly have either two, four or six-drive motors. Individuals who use an R/C car as a basis for their robot use rack and pinion steering where one motor is connected to a drive train and the other (usually a servo motor) is used for steering. Increasing the number of drive motors helps the robot to climb steeper inclines by increasing the torque.

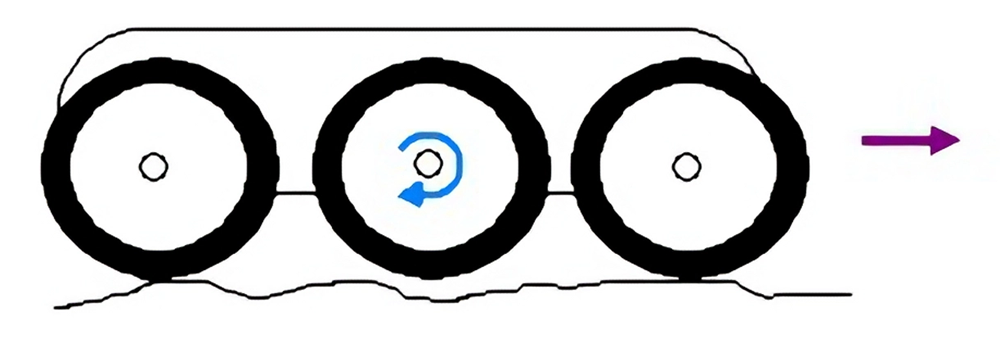

Adding “idle” wheels (wheels not connected to a motor) often has the unfortunate consequence of removing weight from the drive wheels resulting in slip and loss of traction. In the image below, the center wheel, chosen mistakenly as the driven wheel, often loses contact with the ground. The way around this is to add suspension.

A track system (or linking all wheels with gears or drive belts) also helps to prevent this from occurring. Tracks are not necessarily a better choice than using multiple-driven wheels. Military tank manufacturers around the world produce both wheeled and tracked tank models and both offer comparable performance. Most users agree that tank tracks look more intimidating, they are far from being a refined method of transportation and have a tendency to "tear up" the ground beneath them. When making a tight turn, or turning on the spot, tank treads encounter significantly more resistance than wheels as both halves are pushed against the ground perpendicularly to the turning radius.

Skid steering (using 2, 4, or 6 wheels)

You can make a self-balancing robot using two wheels, or a more stable platform using four or more.

2 driven wheels + one or two idler wheels

The two drive wheels are used to propel and turn the robot (skid steering) and the one or two idler wheels to prevent the robot from falling forward or backward. The "idler" wheel can be a caster, a ball, or a monowheel.

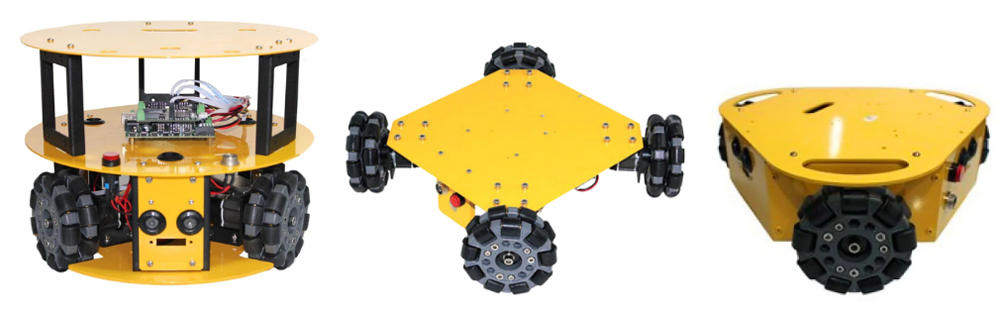

Omni wheels

Usually, have three arranged in a triangular pattern, or four arranged at 90 degrees. Omni wheels have small free-spinning roller wheels on the outside diameter. The central wheel is usually driven. This allows the wheel to be driven forward but slips sideways.

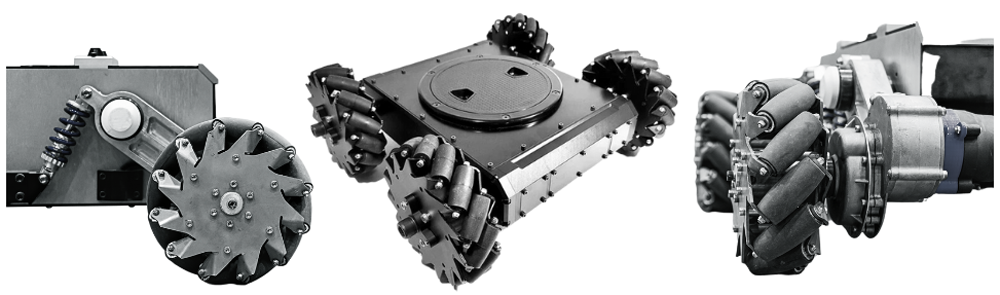

Mecanum

These currently need two pairs of specific wheels arranged on two left and 2 right. Each wheel pulls the robot at an angle instead of purely forward and as such, you can get a variety of additional motions above and beyond that of a normal 4WD robot.

Tri-Star Design

A variant of the "wheel" design would be the tri-star. This design places three wheels of equal diameter about the axis of rotation. Normally these wheels are all driven via a pulley from a central shaft. It can be argued that the added complexity of this design allows it to overcome large obstacles. Not many robots incorporate this design as of yet.

Robots with large wheels are often more eye-catching than robots with small wheels, but don't let looks affect your design! The right wheel size is very important and care should be taken to choose the right one for each specific robot. Two main equations need to be considered:

(forward) velocity = angular velocity (of the wheel) x radius (of the wheel)

This means that both the radius of the wheel and the angular speed at which it's turning will affect the forward velocity.

force (exerted by the wheel on the surface) = torque (of the motor) / radius (of the wheel)

For a wheeled robot to move or climb an incline, the wheel exerts a horizontal force on the surface. If you need to exert a high force (because your robot is heavy), then you need to increase either the torque or decrease the radius of the wheel. Increasing the torque is usually expensive, and increasing the radius usually means a heavier wheel, requiring more torque, but also reducing the maximum speed (since they have to rotate faster). Very small wheel diameters may also be impractical.

Choosing the right grip is all about maximizing the contact area. If your robot will be traveling on a ceramic or wood floor, a flat rubber tire will provide the most grip, since both surfaces are very flat. If you also want it to roll on the carpet, then you might add a small tread, but nothing too deep. At the opposite extreme, if you want your robot to get through deep mud and dirt, you would choose a tire with deep grooves to "scoop" the mud away to move forward.

What happens when you use a tire with a deep tread on a flat surface? There is almost no contact between the tire and the floor, so it's a lot easier for the tire to lose traction. What about a flat tire in the mud? There are certainly a lot of contacts, but without a "shovel" effect, the wheel will just spin in place.